I’ve been running Ubuntu on my Framework 13 for a while now without any major issues. However, my initial setup restricted me to a deep sleep suspend that will drain your battery in a day or two if you forget about it. As I anyhow needed to reinstall my system to get Ubuntu 23.04 going, I decided to mix it up a bit.

My setup is simple and has only a few requirements. First of all, a full disk encryption is a must. Secondly, ZFS is non-negotiable. And lastly, it would be nice to have hibernation this time round.

When it comes to full disk encryption with ZFS, there is an option of native ZFS encryption. And indeed, I’ve done setups with it before. However, getting hibernation running on top of ZFS was not something I managed to get running properly.

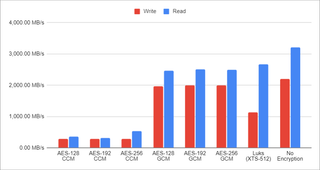

For hibernation, I really prefer to have a separate swap partition encrypted using Luks. And, if you use both Luks and native ZFS encryption, you get asked for the encryption passphrase twice. Since I’m too lazy for that, I decided to have ZFS on top of the Luks, like in the good old days. Performance-wise it’s awash anyhow. Yes, writing is a bit slower on artificial tests but in reality, the difference is negligible.

Avid readers of my previous installation guides will already know that my personal preferences are really noticeable in these guides. For example, I like my partitions set up a certain way and I will always nuke the dreadful snap system.

Honestly, if you are ok with the default Ubuntu setup, or just uncomfortable with the command line, you might want to stop reading and simply follow the official Framework 13 installation guide. It’s a great guide and the final result is something 99% of people will be happy with.

The first step is to boot into the “Try Ubuntu” option of the USB installation. Once we have a desktop, we want to open a terminal. And, since all further commands are going to need root credentials, we can start with that.

sudo -i

Next step should be setting up a few variables - disk, pool name, hostname, and username. This way we can use them going forward and avoid accidental mistakes. Just make sure to replace these values with ones appropriate for your system.

DISK=/dev/disk/by-id/<diskid>

POOL=<poolname>

HOST=<hostname>

USER=<username>

For this setup, I wanted 4 partitions. The first two partitions will be unencrypted and in charge of booting. While I love encryption, I decided not to encrypt the boot partition in order to make my life easier as you cannot integrate the boot partition password prompt with the later data password prompt thus requiring you to type the password twice (or trice if you decide to use native ZFS encryption on top of that). Both swap and ZFS partition are fully encrypted.

Also, my swap size is way too excessive since I have 64 GB of RAM and I wanted to allow for hibernation under the worst of circumstances (i.e., when RAM is full). Hibernation usually works with much smaller partitions but I wanted to be sure and my disk

Also, my swap size is way too excessive since I have 64 GB of RAM and I wanted to allow for hibernation under the worst of circumstances (i.e., when RAM is full). Hibernation usually works with much smaller partitions but I wanted to be sure and my disk was big enough to accommodate.

Lastly, while blkdiscard does nice job of removing old data from the disk, I would always recommend also using dd if=/dev/urandom of=$DISK bs=1M status=progress if your disk was not encrypted before.

blkdiscard -f $DISK

sgdisk --zap-all $DISK

sgdisk -n1:1M:+63M -t1:EF00 -c1:EFI $DISK

sgdisk -n2:0:+960M -t2:8300 -c2:Boot $DISK

sgdisk -n3:0:+64G -t3:8200 -c3:Swap $DISK

sgdisk -n4:0:0 -t4:8309 -c4:ZFS $DISK

sgdisk --print $DISK

Once partitions are created, we want to setup our LUKS encryption. Here you will notice I use luks2 headers with a few arguments helping with nVME performance.

cryptsetup luksFormat -q --type luks2 \

--perf-no_write_workqueue --perf-no_read_workqueue \

--cipher aes-xts-plain64 --key-size 256 \

--pbkdf argon2i $DISK-part4

cryptsetup luksFormat -q --type luks2 \

--perf-no_write_workqueue --perf-no_read_workqueue \

--cipher aes-xts-plain64 --key-size 256 \

--pbkdf argon2i $DISK-part3

Since creating encrypted partition doesn’t mount them, we do need this as a separate step. Since the swap partition will be the first one to load, I will give it a name of the host in order to have a bit nicer password prompt.

cryptsetup luksOpen $DISK-part4 zfs

cryptsetup luksOpen $DISK-part3 $HOST

Finally, we can set up our ZFS pool with an optional step of setting quota to roughly 80% of disk capacity. Adjust the exact values as needed.

zpool create -o ashift=12 -o autotrim=on \

-O compression=lz4 -O normalization=formD \

-O acltype=posixacl -O xattr=sa -O dnodesize=auto -O atime=off \

-O canmount=off -O mountpoint=none -R /mnt/install \

$POOL /dev/mapper/zfs

zfs set quota=1.5T $POOL

I used to be a fan of using just a main dataset for everything, but these days I use a more conventional “separate root dataset” approach.

zfs create -o canmount=noauto -o mountpoint=/ $POOL/Root

zfs mount $POOL/Root

And a separate home partition will not be forgotten.

zfs create -o canmount=noauto -o mountpoint=/home $POOL/Home

zfs mount $POOL/Home

zfs set canmount=on $POOL/Home

With all datasets in place, we can finish setting the main dataset properties.

zfs set devices=off $POOL

Now it’s time to format the swap.

mkswap /dev/mapper/$HOST

And then the boot partition.

yes | mkfs.ext4 $DISK-part2

mkdir /mnt/install/boot

mount $DISK-part2 /mnt/install/boot

And finally, the EFI partition.

mkfs.msdos -F 32 -n EFI -i 4d65646f $DISK-part1

mkdir /mnt/install/boot/efi

mount $DISK-part1 /mnt/install/boot/efi

At this time, I also sometime disable IPv6 as I’ve noticed that on some misconfigured IPv6 networks it takes ages to download packages. This step is both temporary (i.e., IPv6 is disabled only during installation) and fully optional.

sysctl -w net.ipv6.conf.all.disable_ipv6=1

sysctl -w net.ipv6.conf.default.disable_ipv6=1

sysctl -w net.ipv6.conf.lo.disable_ipv6=1

To start the fun we need debootstrap package. Starting this step, you must be connected to the Internet.

apt update && apt install --yes debootstrap

Bootstrapping Ubuntu on the newly created pool comes next. This will take a while.

debootstrap lunar /mnt/install/

We can use our live system to update a few files on our new installation.

echo $HOST > /mnt/install/etc/hostname

sed "s/ubuntu/$HOST/" /etc/hosts > /mnt/install/etc/hosts

sed '/cdrom/d' /etc/apt/sources.list > /mnt/install/etc/apt/sources.list

cp /etc/netplan/*.yaml /mnt/install/etc/netplan/

If you are installing via WiFi, you might as well copy your wireless credentials. Don’t worry if this returns errors - that just means you are not using wireless.

mkdir -p /mnt/install/etc/NetworkManager/system-connections/

cp /etc/NetworkManager/system-connections/* /mnt/install/etc/NetworkManager/system-connections/

At last, we’re ready to “chroot” into our new system.

mount --rbind /dev /mnt/install/dev

mount --rbind /proc /mnt/install/proc

mount --rbind /sys /mnt/install/sys

chroot /mnt/install \

/usr/bin/env DISK=$DISK USER=$USER \

bash --login

With our newly installed system running, let’s not forget to set up locale and time zone.

locale-gen --purge "en_US.UTF-8"

update-locale LANG=en_US.UTF-8 LANGUAGE=en_US

dpkg-reconfigure --frontend noninteractive locales

dpkg-reconfigure tzdata

Now we’re ready to onboard the latest Linux image.

apt update

apt install --yes --no-install-recommends \

linux-image-generic linux-headers-generic

Followed by the boot environment packages.

apt install --yes \

zfs-initramfs cryptsetup keyutils grub-efi-amd64-signed shim-signed

Now we set up crypttab so our encrypted partitions are decrypted on boot.

echo "$HOST PARTUUID=$(blkid -s PARTUUID -o value $DISK-part3) none \

swap,luks,discard,initramfs,keyscript=decrypt_keyctl" >> /etc/crypttab

echo "zfs PARTUUID=$(blkid -s PARTUUID -o value $DISK-part4) none \

luks,discard,initramfs,keyscript=decrypt_keyctl" >> /etc/crypttab

cat /etc/crypttab

To mount all those partitions, we also need some fstab entries. The last entry is not strictly needed. I just like to add it in order to hide our LUKS encrypted ZFS from the file manager.

echo "UUID=$(blkid -s UUID -o value /dev/mapper/$HOST) \

swap swap defaults 0 0" >> /etc/fstab

echo "PARTUUID=$(blkid -s PARTUUID -o value $DISK-part2) \

/boot ext4 noatime,nofail,x-systemd.device-timeout=5s 0 1" >> /etc/fstab

echo "PARTUUID=$(blkid -s PARTUUID -o value $DISK-part1) \

/boot/efi vfat noatime,nofail,x-systemd.device-timeout=5s 0 1" >> /etc/fstab

echo "/dev/disk/by-uuid/$(blkid -s UUID -o value /dev/mapper/zfs) \

none auto nosuid,nodev,nofail 0 0" >> /etc/fstab

cat /etc/fstab

On systems with a lot of RAM, I like to adjust swappiness a bit. This is inconsequential in the grand scheme of things, but I like to do it anyhow.

echo "vm.swappiness=10" >> /etc/sysctl.conf

Now we create the boot environment.

KERNEL=`ls /usr/lib/modules/ | cut -d/ -f1 | sed 's/linux-image-//'`

update-initramfs -c -k $KERNEL

And then, we can get grub going. Do note we also set up booting from swap (needed for hibernation) here too. Since we’re using secure boot, bootloaded-id HAS to be Ubuntu.

sed -i "s/^GRUB_CMDLINE_LINUX_DEFAULT.*/GRUB_CMDLINE_LINUX_DEFAULT=\"quiet splash \

nvme.noacpi=1 \

module_blacklist=hid_sensor_hub \

RESUME=UUID=$(blkid -s UUID -o value /dev/mapper/$HOST)\"/" \

/etc/default/grub

update-grub

grub-install --target=x86_64-efi --efi-directory=/boot/efi --bootloader-id=Ubuntu \

--recheck --no-floppy

And now, finally, we can install our desktop environment.

apt install --yes ubuntu-desktop-minimal

Once the installation is done, I like to remove snap and banish it from ever being installed.

apt remove --yes snapd

echo 'Package: snapd' > /etc/apt/preferences.d/snapd

echo 'Pin: release *' >> /etc/apt/preferences.d/snapd

echo 'Pin-Priority: -1' >> /etc/apt/preferences.d/snapd

Since Firefox is only available as snapd package, we can install it manually.

add-apt-repository --yes ppa:mozillateam/ppa

cat << 'EOF' | sed 's/^ //' | tee /etc/apt/preferences.d/mozillateamppa

Package: firefox*

Pin: release o=LP-PPA-mozillateam

Pin-Priority: 501

EOF

apt update && apt install --yes firefox

For Framework Laptop I use here, we need one more adjustment due to Dell audio needing special care. In addition, you might want to mess with WiFi power save modes a bit.

echo "options snd-hda-intel model=dell-headset-multi" >> /etc/modprobe.d/alsa-base.conf

sed '/s/wifi.powersave =.*/wifi.powersave = 2/' \

/etc/NetworkManager/conf.d/default-wifi-powersave-on.conf

Of course, we need to have a user too.

adduser --disabled-password --gecos '' $USER

usermod -a -G adm,cdrom,dialout,dip,lpadmin,plugdev,sudo,tty $USER

echo "$USER ALL=NOPASSWD:ALL" > /etc/sudoers.d/$USER

passwd $USER

I like to add some extra packages and do one final upgrade before dealing with the sleep stuff.

add-apt-repository --yes universe

apt update && apt dist-upgrade --yes

The first portion is setting up the whole suspend-then-hibernate stuff. This will make Ubuntu to do normal suspend first. If suspended for 20 minutes, it will quickly wake up and do the hibernation then.

sed -i 's/.*AllowSuspend=.*/AllowSuspend=yes/' \

/etc/systemd/sleep.conf

sed -i 's/.*AllowHibernation=.*/AllowHibernation=yes/' \

/etc/systemd/sleep.conf

sed -i 's/.*AllowSuspendThenHibernate=.*/AllowSuspendThenHibernate=yes/' \

/etc/systemd/sleep.conf

sed -i 's/.*HibernateDelaySec=.*/HibernateDelaySec=20min/' \

/etc/systemd/sleep.conf

And lastly, the whole sleep setup is nothing if we cannot activate it. Closing the lid seems like a perfect place to do it.

apt install -y pm-utils

sed -i 's/.*HandleLidSwitch=.*/HandleLidSwitch=suspend-then-hibernate/' \

/etc/systemd/logind.conf

sed -i 's/.*HandleLidSwitchExternalPower=.*/HandleLidSwitchExternalPower=suspend-then-hibernate/' \

/etc/systemd/logind.conf

It took a while but we can finally exit our debootstrap environment.

exit

Let’s clean all mounted partitions and get ZFS ready for next boot.

umount /mnt/install/boot/efi

umount /mnt/install/boot

mount | grep -v zfs | tac | awk '/\/mnt/ {print $3}' | xargs -i{} umount -lf {}

umount /mnt/install

zpool export -a

After reboot, we should be done and our new system should boot with a password prompt.

reboot

Once we log into it, we still need to adjust boot image and grub, followed by a hibernation test. If you see your desktop in the same state as you left it after waking the computer up, all is good.

sudo update-initramfs -u -k all

sudo update-grub

sudo systemctl hibernate

If you get Failed to hibernate system via logind: Sleep verb "hibernate" not supported, go into BIOS and disable secure boot (Enforce Secure Boot option). Unfortunately, the secure boot and hibernation still don’t work together but there is some work in progress to make it happen in the future. At this time, you need to select one or the other.

PS: Just setting HibernateDelaySec as in older Ubuntu versions doesn’t work with the current Ubuntu anymore due to systemd bug. Hibernation is only going to happen when the battery reaches 5% of capacity instead of at a predefined time. This was corrected in v253 but I doubt Ubuntu 23.04 will get that update. I’ll leave it in the guide as it’ll likely work again in Ubuntu 23.10.

PPS: If battery life is really precious to you, you can go to hibernate directly by setting HandleLidSwitch=suspend-then-hibernate. Alternatively, you can look into setting mem_sleep_default=deep in the Grub.

PPPS: There are versions of this guide (without hibernation though) using the native ZFS encryption for the other Ubuntu versions: 22.04, 21.10, and 20.04. For LUKS-based ZFS setup, check the following posts: 22.10, 20.04, 19.10, 19.04, and 18.10.